Torii Ryūzō and the Nature of Early Anthropological Photography

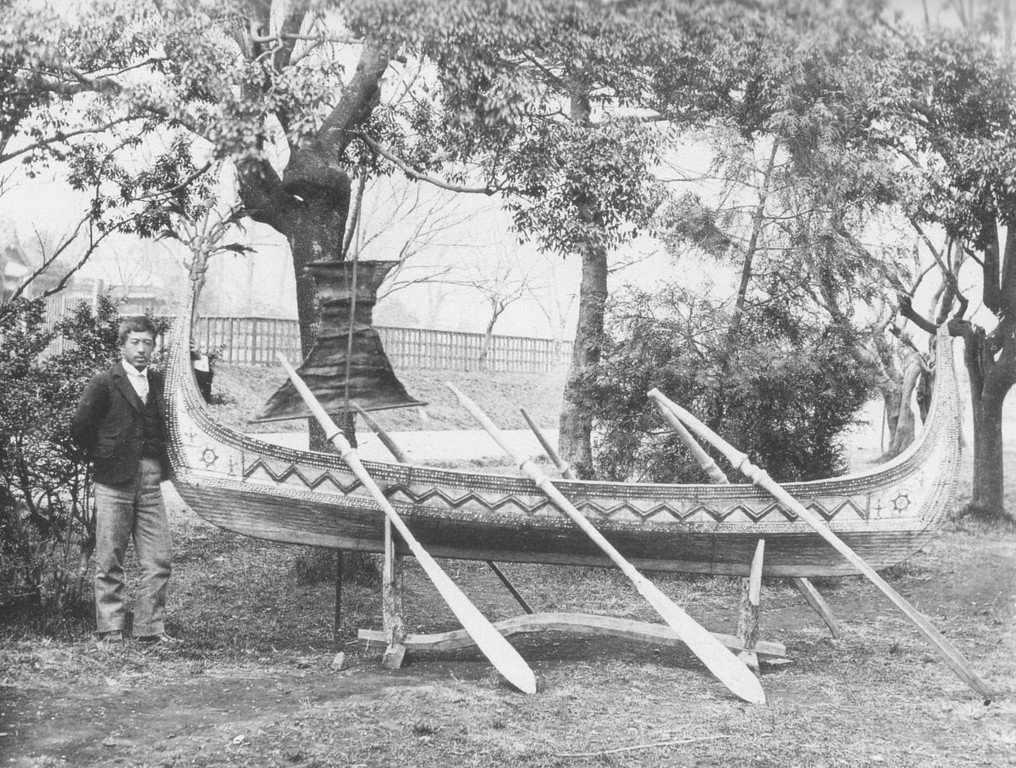

Torii with the Yami canoe, 1897. Photographer uncredited.

This lecture focused on anthrology and, specifcally, Torii Ryūzō's (1870–1953) work. The photographs are notable in that many appeared staged, often with Torii in them, either for scale or as part of the images in a kind of early photographical ‘look where I am’. His life and work also overlapped with Mori Ushinosuke (1877–1926) as both pioneered photography as part of their research and both covered Taiwanese indigeonious’ peoples.

There are some interesting aspects, not just to the practises of anthology but also, specifically, the history of early photography. We exist now in an age when we are both fortunately to have devices which allow access to humanity’s vast stores of knowledge, to work out a maths equation or take stunning photographs.

Being in my forties, I grew up with film-based mirrored cameras, being limited to 24 image films and having to pay to send them away to be developed, or to use (as I did at college) darkrooms. Now I have a phone with a camera which can allow me to take not only film but video at high definition and instantly. I take lots of dog and cat related pictures and photography is one of my passions.

So, imagine plate-based photography, which involves standing still for long periods, hefting heavy equipment and needing specialist training to use it. An analogue can be made with modern mirrored , and digital, cameras as many with expensive lenses can cost a lot of money, be heavy but you also need to know how to work them. While modern cameras are infinitely easier, taking such a piece of technology to a remote place, along with someone skilled enough to operate that techology really hammers home how important photography was to early anthropological studies.

The other issue is the framing of these photographs. Modern anthropology is about documenting whilst the documetor remains unseen and, most importantly, attempts to record events without contamininating. It is very safe to say this is now how Torii Ryūzō operated as he, his assistances and associates, appear in many of the surviving photographs, as well as having many being obviously staged rather than documenting the lives of these tribes in a more natural and authentic setting.

Take, for example, the photograph at the top of this blog post. It was one of several we examined during the course of this lecture. It is also one of them most obviously staged with a three-person canoe removed from the water, transported and then propped up in a more aesthetic setting with Torii to its left, showing off, in western clothing. There is no sign of the canoeists, the indigineous people, water and the only thing which places the image at all is the canoe’s unqiue design and the Japanese anthropologist standing next to it. There are no clues to where in the world this is being taken and an obvious amount of work has been put into staging it.

At the same time, because Torii is in the photograph, the next logical question is: who is taking the photograph? No one is, according to the reading, credited and Torii himself feels like the focus of the image, with the canoe serving as window-dressing. The focus is on him, not on the Yami tribe, outside the curiosity of one of their canoes.

The other question worth discussing is how much of Japanese anthropological research was taken from western practices. Torii is in western clothing and this picture taken during the Meiji Restoration and the Era (1868–1912), a period when western culture was in vogue and kimono and traditional clothing gave way to fashions more familiar in Europe, England and America. Similarly, we can assume that some of their practices were also adapted, though Torii was active as an anthropologist well into the twentieth century. Fortunately modern anthropology is much more advanced, as well as more respectful of subject matter, cultures and practices.

Image credit:

Ka F. Wong (2004) Entanglements of ethnographic images: Torii Ryūzō’s photographic record of Taiwan aborigines (1896–1900), Japanese Studies, 24:3, 283-299.